Matt Keracher, PR and Campaigns Executive at RSPH, looks at the relationship between happiness and human health and wellbeing.

On a recent visit to London, my Mum and I were chatting over a glass of wine about her aspirations for me and my older sister when we were growing up in rural Lincolnshire. Her answer surprised me somewhat and got me thinking. She said her maternal ambitions for a long time were for her children to grow up, get a good education, secure a well-paid job and to become materially successful.

However, as time has gone by, she increasingly has only one wish for us, one thing that was far more important than any accumulation of material wealth, one thing that supersedes all else; for us to be happy. My Mum’s revelation made me really think; what constitutes happiness? How can happiness be achieved? And, from a public health perspective, how significant is happiness in relation to human health and wellbeing?

It has long been known that too much stress can make a person physically unwell. Chronic stress can lower immunity, leaving people more susceptible to infections. Similarly, stress has been shown to contribute to the development of high blood pressure and heart disease.

So, if stress can make you ill, surely happiness can make you healthy? Increasingly, this looks like it may be the case. Martin Seligman, Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, points to a study of 180 nuns in Milwaukee. The study revealed that happy nuns lived longer than their gloomy counterparts by an average of 9 years. Further to this, a 2007 study of more than 6000 men and women found emotional vitality—a sense of enthusiasm, of hopefulness, of engagement in life, and the ability to face life’s stresses with emotional balance—appears to reduce the risk of coronary heart disease.

A growing body of evidence indicates that happiness is a major factor in disease prevention and longer life expectancy. So what can we do as individuals to make ourselves happy?

Estimates suggest that 50 per cent of happiness is related to genetics, which is out of our control. 10 per cent is dependent on life circumstances and situation. The remaining 40 per cent of how happy we are is completely subject to self-control and our personal internal state of mind. This gives everyone a great opportunity to take control of their own happiness by making choices that can ultimately lead to a happier mind and healthier body. Regular exercise is known to reduce anxiety and improve sleep patterns, and studies conducted on rats indicate that exercise mimics the effects of antidepressants on the brain.

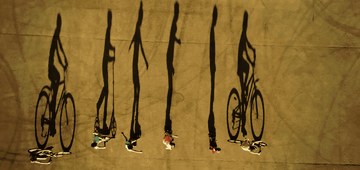

Those with close relationships to friends and family tend to be happier, as do those who spend less time commuting to and from work. Meditation and spending more time outside have also been shown to increase people’s level of happiness. From a public health perspective, if we know happiness is linked to physical health, why are we not pursuing happiness as a health policy?

Everyone wants to be happy. Everyone should have the right to be happy. It’s the duty of our government and health institutions to give people every opportunity to achieve happiness. A health policy based on the pursuit of happiness would not only benefit the public’s health and wellbeing, but also contribute to making people more economically productive, more creatively productive and allow people to live longer, more fulfilled lives. It seems to me that if increasing happiness is made the end goal, much of the rest takes care of itself.

References

i Deborah D. Danner, David A. Snowdon, and Wallace V. Friesen. 2000. Positive Emotions in Early Life and Longevity: Findings from the Nun Study. [Online]. [Accessed Feb 2015]. Available from: https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/psp805804.pdf

ii Rimer, S. 2011. Happiness and Health: The biology of emotion—and what it may teach us about helping people to live longer. [Online]. [Accessed Feb 2015]. Available from: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/magazine/happiness-stress-heart-disease/